YOUR WATER

History

YOUR WATER SYSTEM

A Chronological History of LA’s Water System

Images Courtesy of California Department Of Water Resources, California State Library, Kcet, LA County Department of Public Works, LA County Flood Control District, Library of Congress, Los Angeles Public Library, Los Angeles Times, Metropolitan Water District, San Francisco Chronicle, Santa Clara Valley Water News, University Of Southern California, U.s. National Archives And Records Administration, and Water Replenishment District.

Los Angeles, it has been said, is an odd place for a big metropolis.

The people who call this place home have been forced to contend with numerous floods, droughts, fires and mudslides (to speak nothing of earthquakes) throughout its 200-year history.

Just over a century ago, we took matters into our own hands and began to manage and manipulate our water supply, stretching it beyond the confines of increasingly insufficient surface and groundwater.

The rise of this region, sociologist Harvey Molotch wrote, “can only be explained as a remarkable victory of human cunning over the so-called limits of nature.”

Our greatest struggle has been with water – how to get more of it, how to save it and what to do with it when it surges all around us.

That struggle, more than any other, is the story of LA County.

1800s

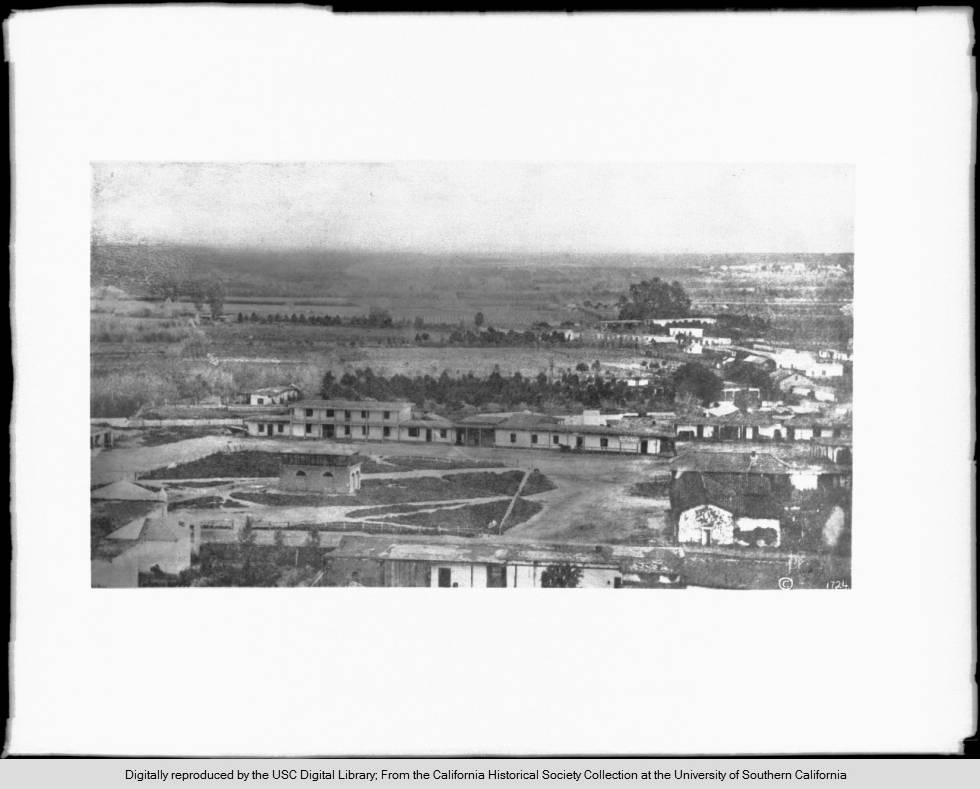

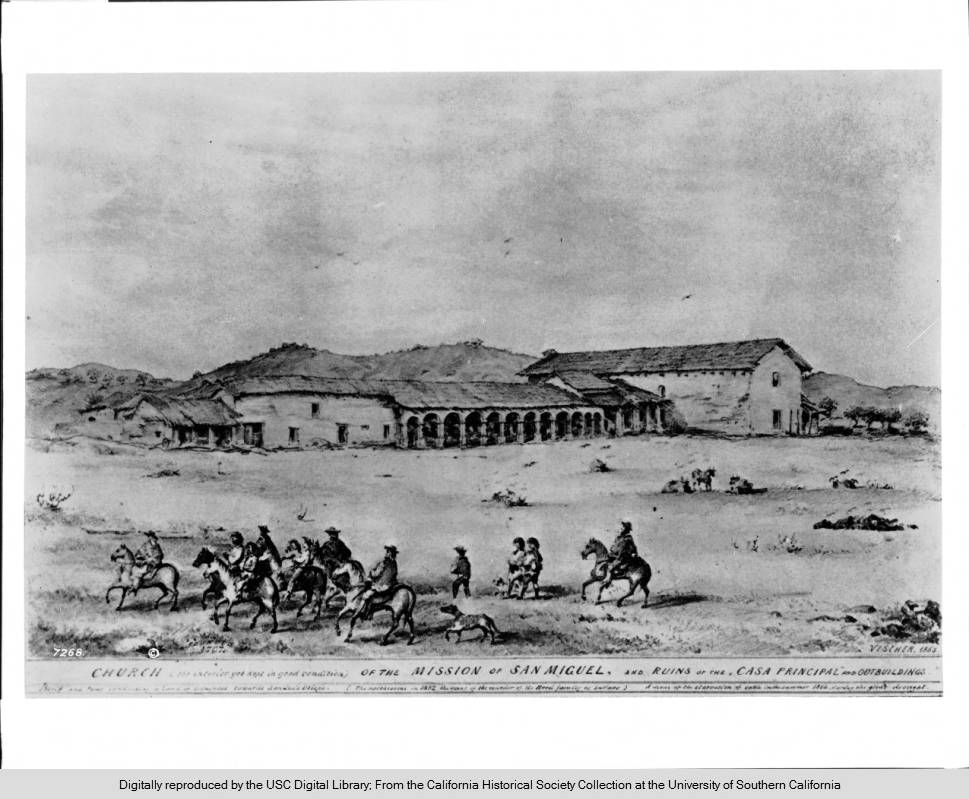

In the early 1800s, Los Angeles is a tiny farming community of a couple hundred people.

Fanning out from the banks of the Los Angeles river, the first Angelenos take advantage of the local surface water – rivers, lakes, streams – for personal and agricultural interests, weathering the unpredictability of living in a dry climate with variable rainfall.

Over time, the growing population cannot consistently rely on surface water due to the unpredictable cycles of extreme flood and drought in the region. This results in a shift toward groundwater pumping to support agricultural activities and general living.

1861

“It never rains in Southern California,” sang the Gibraltan songwriter Albert Hammond, “But it pours, man it pours.” There’s a bit of truth in that. Although Los Angeles receives, on average, 15 inches of rainfall per year, the region regularly sees spurts of rain that falls in large quantities all at once.

By 1861, LA County is a community of a little over 4,000 residents. After two dry decades, farmers and ranchers are desperate for rain. On Christmas Eve, it begins to rain, and doesn’t stop for 45 days. Whole towns in Southern California are washed away. Thousands of cattle drown, fruit trees and vineyards are ripped from the ground. At least a quarter of all taxable land in the state is destroyed. LA County itself sees over 66 inches of rainfall. The basin is so inundated with water that large lakes form throughout, with little islands of higher ground peeking out.

In the wake of 1861s historic flood, LA County recovers and the cattle industry – the backbone of the region’s economy – flourishes again in lush, rain-soaked fields.

1862

Bounty quickly turns to misery as Southern California is plunged into an intense drought from 1862-1864.

With no water infrastructure in place to store the rains from 1861, the lack of rainfall over these two years utterly devastates the region. By the Great Drought’s end, LA County’s cattle industry is ruined, suffering the loss of over 70% of its herds.

1884

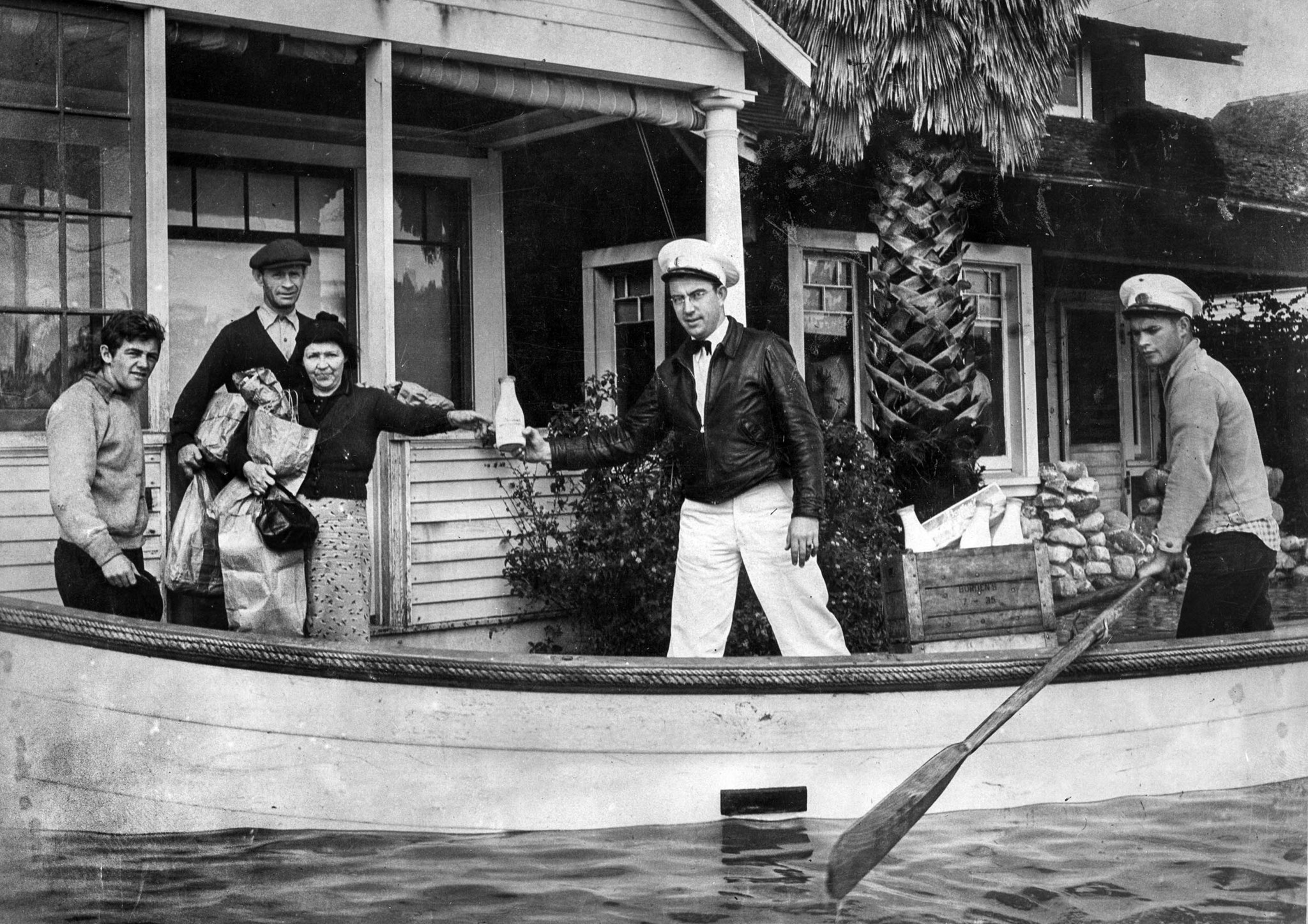

A flash flood on February 17, the culmination of a three-week deluge, leaves one-third of downtown Los Angeles underwater for hours.

According to one first-hand account: “Houses, torn from their foundations, floated downstream with the smoke still escaping from their chimneys. Horses, cows, sheep and now and then the ghastly form of a human being, were part of that strange driftwood. Sometimes the water came in waves 15 feet high.” Bridges are torn apart and swept away. Telegraphs and newly constructed railroad lines are suspended. Hundreds are suddenly left homeless. Many others face financial ruin.

The year will be the wettest on record, as one storm after another pounds the region until May. The Los Angeles River becomes so engorged, it splits into two, with one flowing west down Ballona Creek, the other heading south and merging with the Rio Hondo and San Gabriel rivers in one muddy torrent. The storms convince LA County to begin its first flood control project, a levee on the west bank of the river.

1886

Another massive flood lays waste to the year-old levee, smashes bridges, buries houses in mud, topples telegraph lines, claims five lives and causes half a million dollars in damages ($13.4 million in today’s money).

1900s

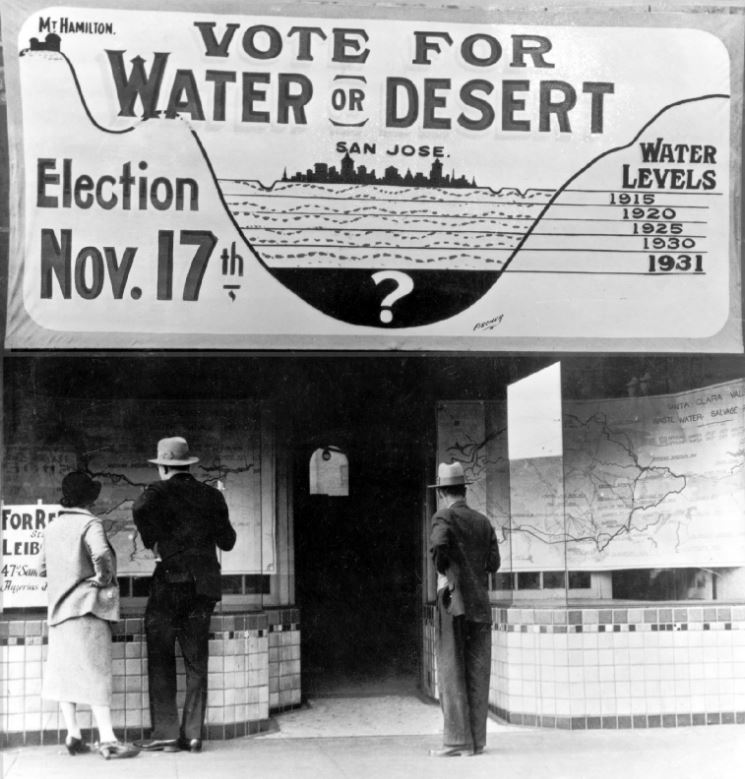

The toll of a rapidly growing population in an arid climate, combined with frequent and costly floods, becomes the impetus for building the early infrastructure of our modern-day water system. Gradually, imported water becomes integral to our water supply and to the health of our groundwater basins. Ultimately, major flooding in the 19th and 20th centuries makes the construction of a complex flood control system in LA County critical to its future.

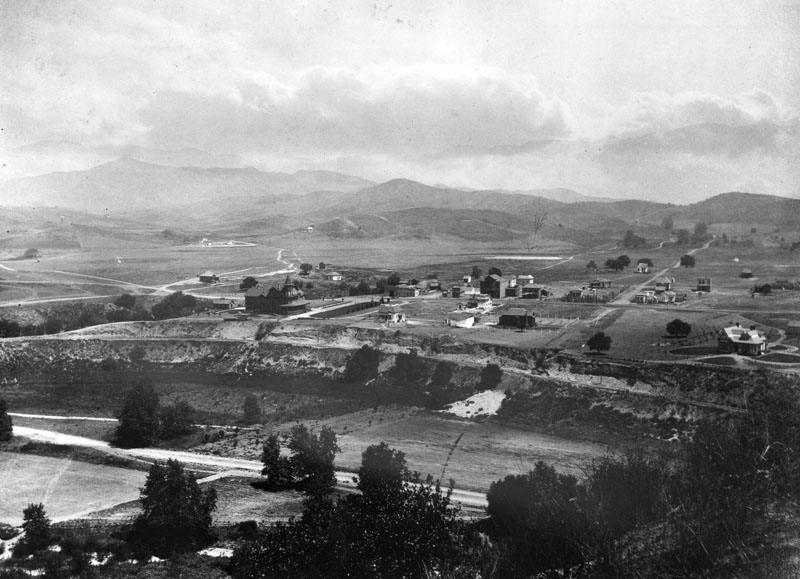

As the region’s aquifers become visibly drained, there is a growing realization that the region must find a new source of freshwater, for both its citizens to drink and its farmers to grow crops. “If you don’t get the water, you won’t need it,” says William Mullholland, the region’s top water engineer.

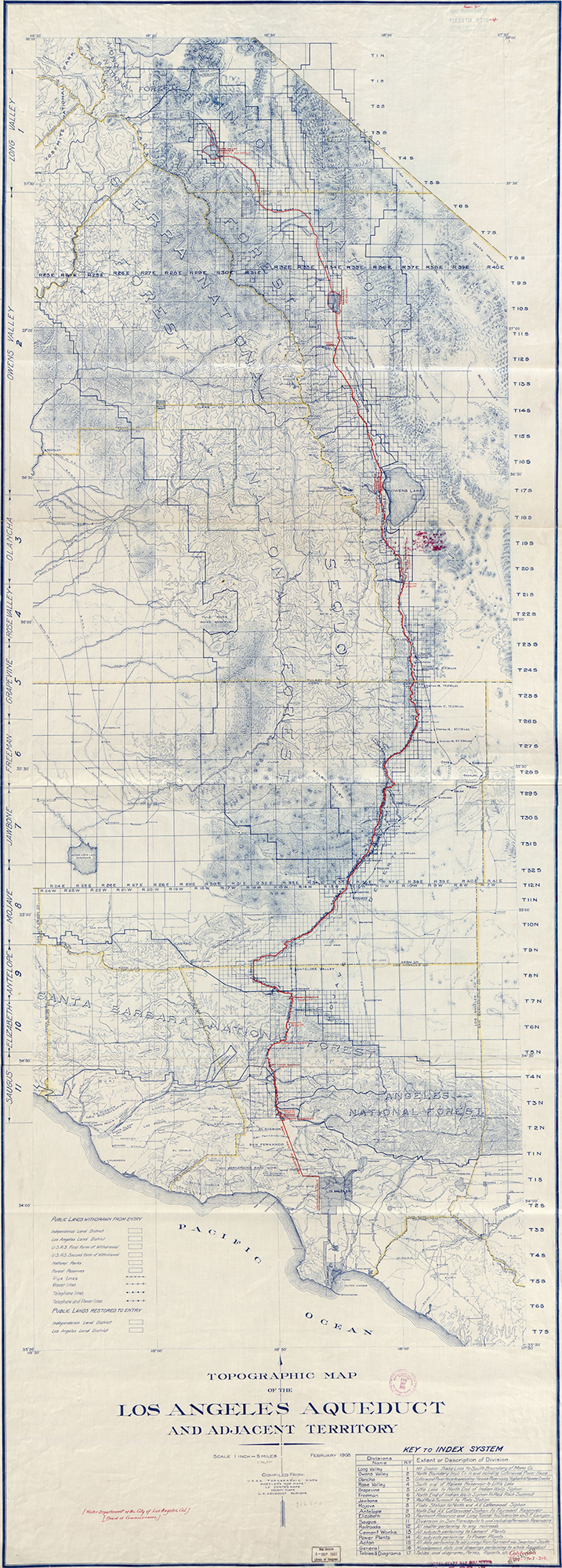

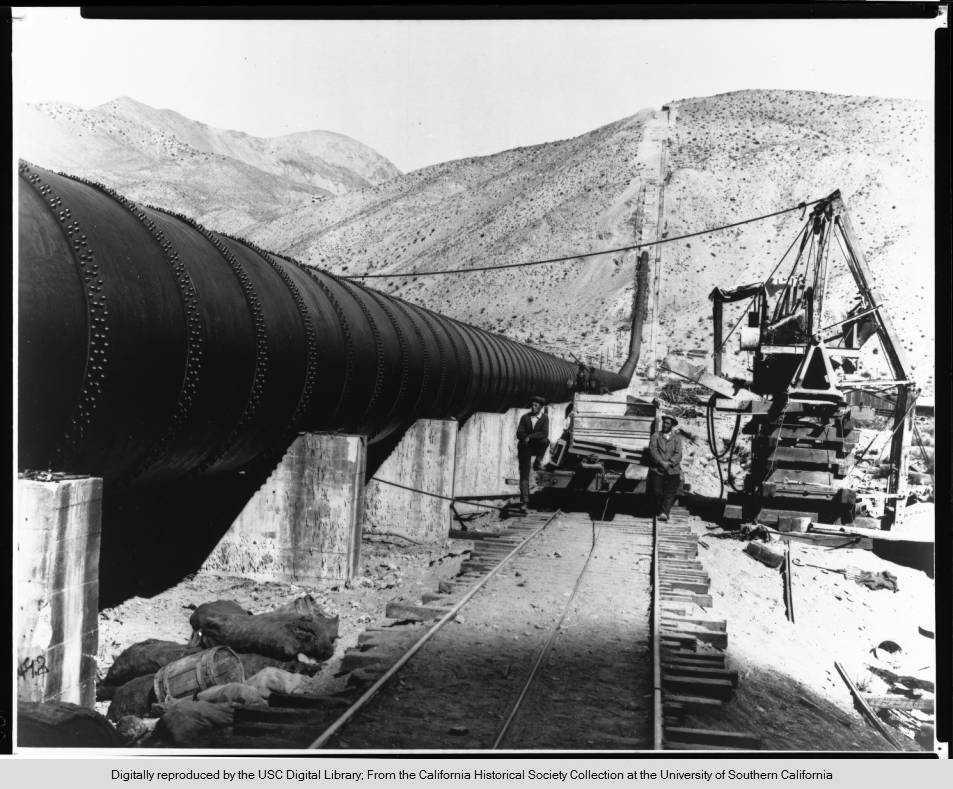

It is Mulholland who, along with former mayor Frederick Eaton, devises a brazen strategy to slake the population’s desperate thirst. The nearest water supply is all the way in the Owens Valley, some 200 miles to the northeast of LA County – a long haul to be sure, but, crucially, mostly a downhill journey, which means that Mulholland can design an aqueduct that will carry the water using nothing but the force of gravity.

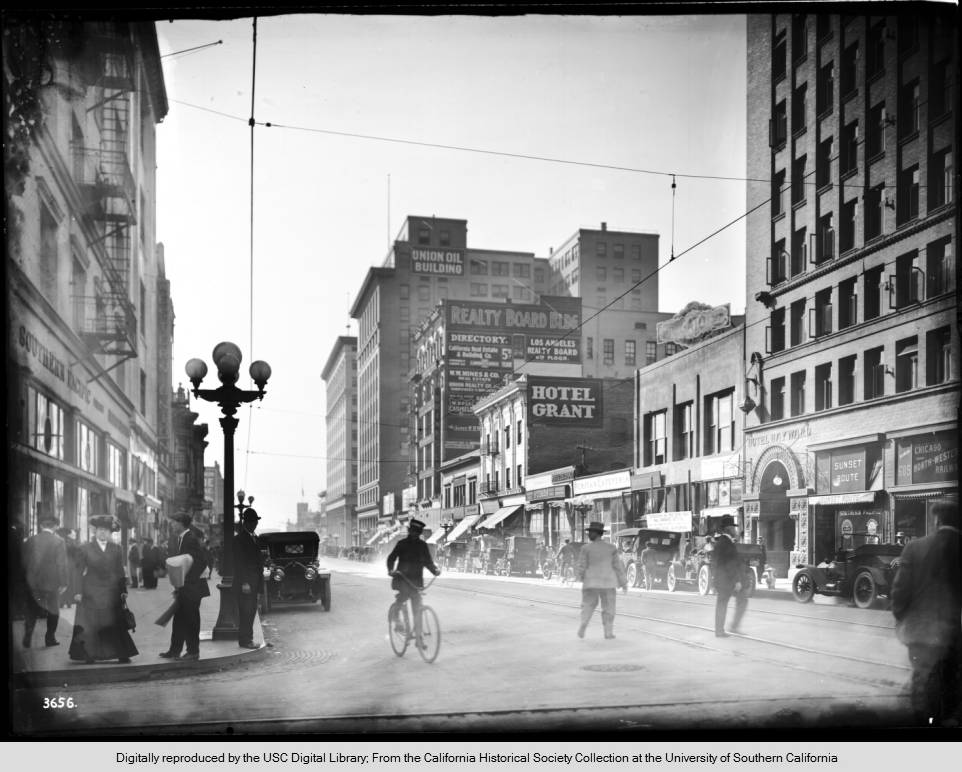

1914

It’s been 30 years since the last major flood. LA County is now home to over half a million people. D.W. Griffith is making movies in the newly-annexed neighborhood of Hollywood. The streets are filled with cars. But water, so scarce in recent years, remains a looming threat to the burgeoning region.

Following years of drought, another flood hits the region. The Los Angeles Times calls the storm that hits the southland in late January “one of the most severe… in the history of Southern California…leaving in its wake complete saturation, demoralized traffic, demolished bridges, undermined houses and uprooted trees.” Rivers spill over, swamping new developments built alongside them. More than 100 homes are lost and at least three people die.

The flood is enough to convince the State Legislature to pass the Flood Control Act in 1915 establishing the Los Angeles County Flood Control District. Over the next decade, taxpayers will approve two bond measures to build a number of dams, the first steps toward curbing the rivers’ destructive potential, but they will not be enough to prevent the devastation to come.

1935

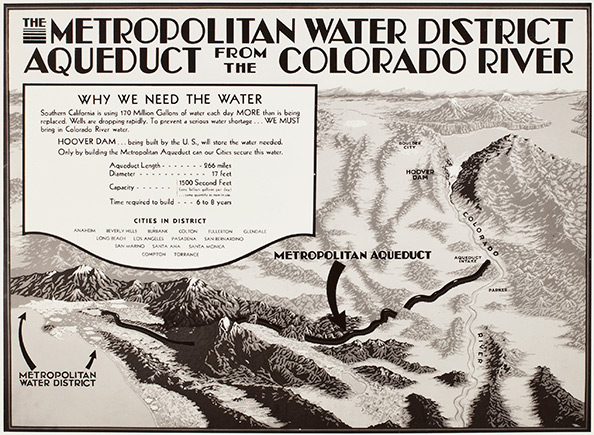

By the 1930s, there are over two million people living in Los Angeles County. Between the food they grow and the water they drink, it becomes clear that the water from the Owens Valley is not enough to sustain the region’s growth.

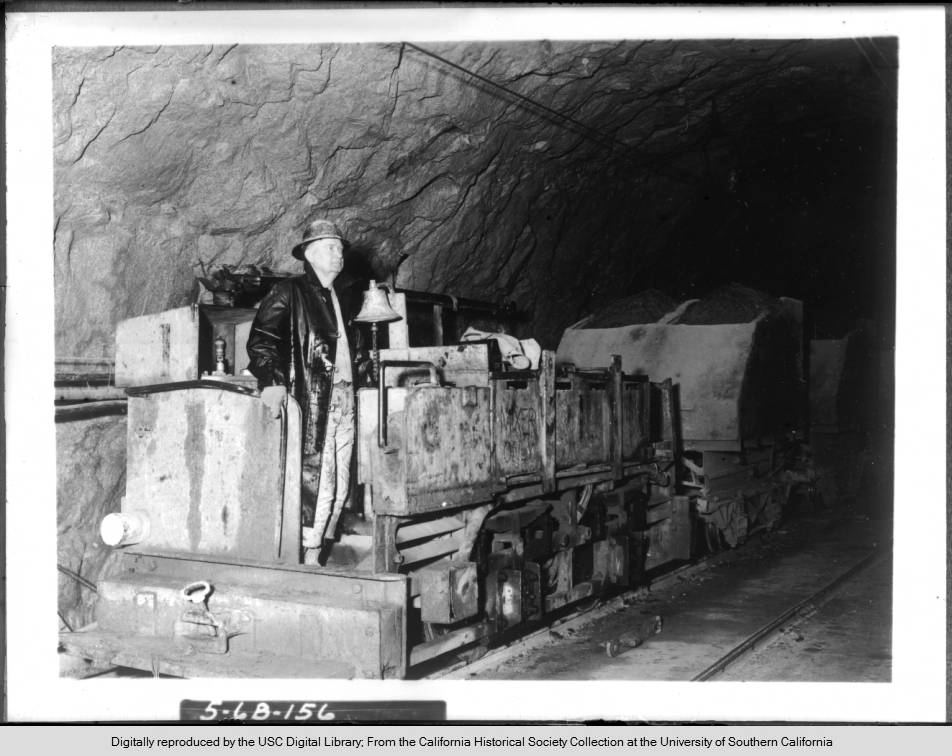

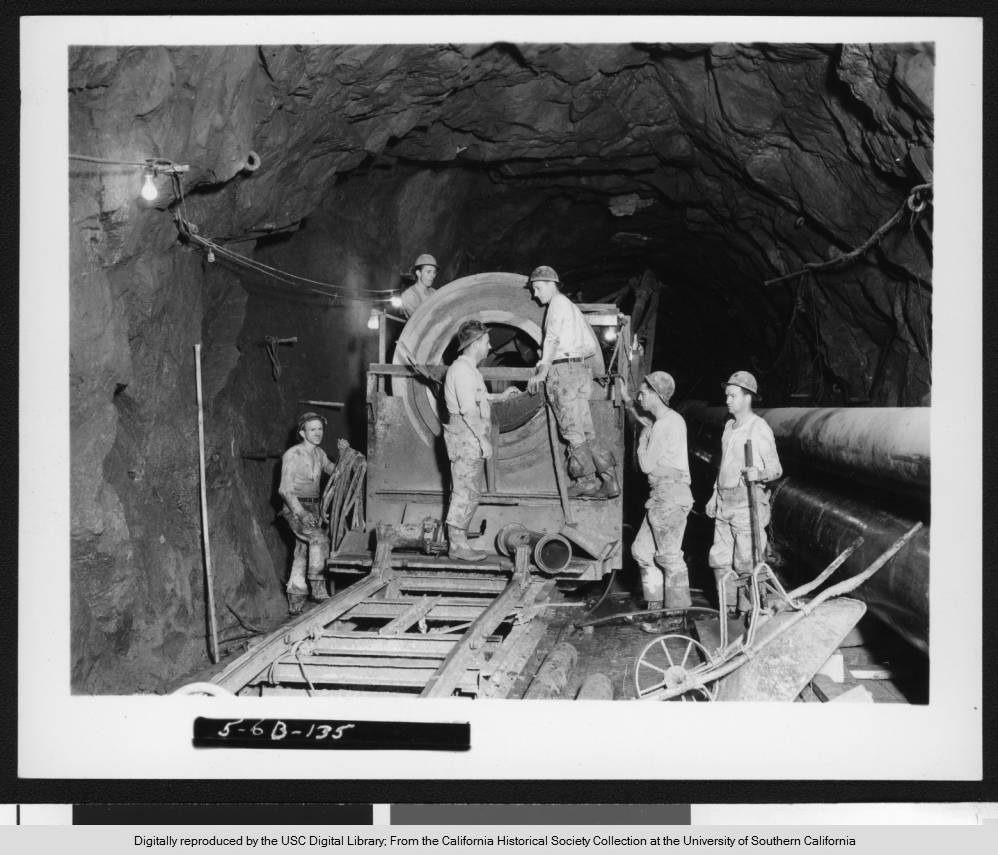

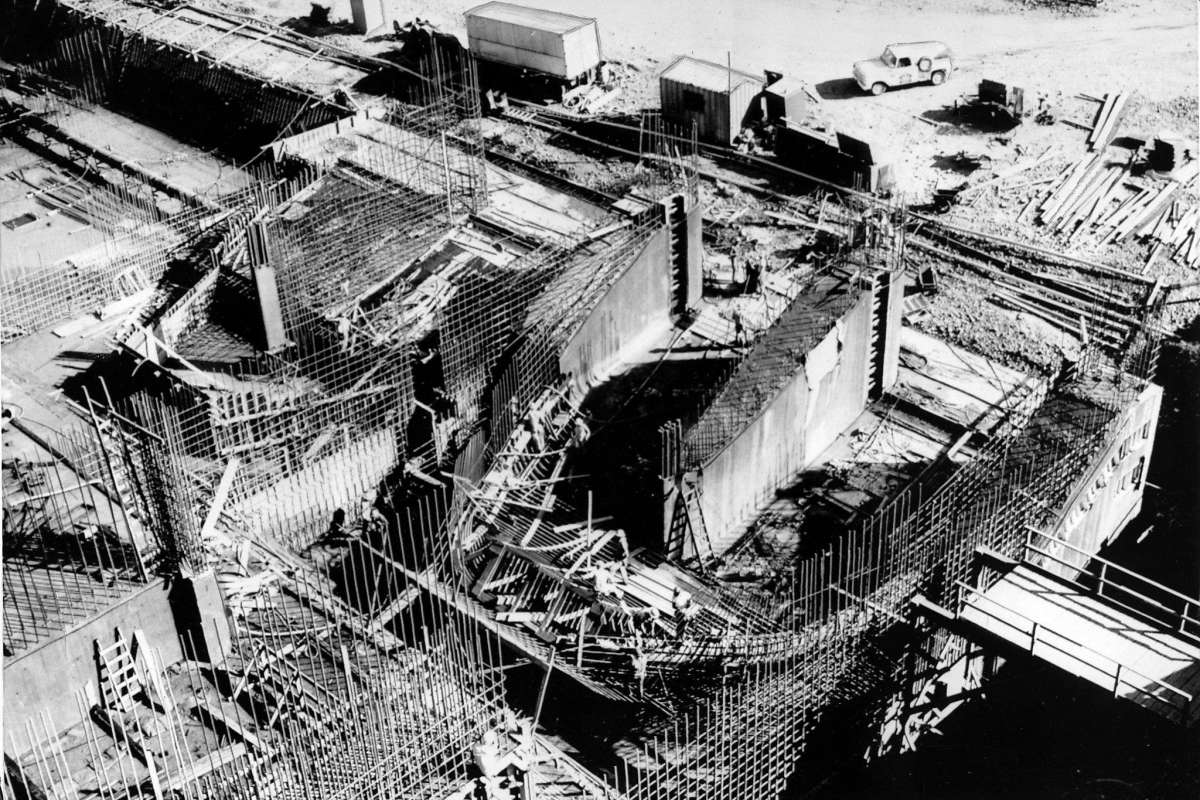

This time, Mullholland, still the top water engineer, shifts his gaze 220 miles eastward to the Colorado River, which runs along California’s eastern border. Eleven cities in Los Angeles and Orange Counties form the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California to build the 242-mile Colorado River Aqueduct, which will carry water from the Colorado River to Southern California.

The project employs roughly 30,000 people and is later declared one of the Seven Engineering Wonders of American Engineering by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

Completed in 1935, operational in 1939, the aqueduct gives California 1.4 trillion gallons of water a year, enough to sustain around 10 million new residents.

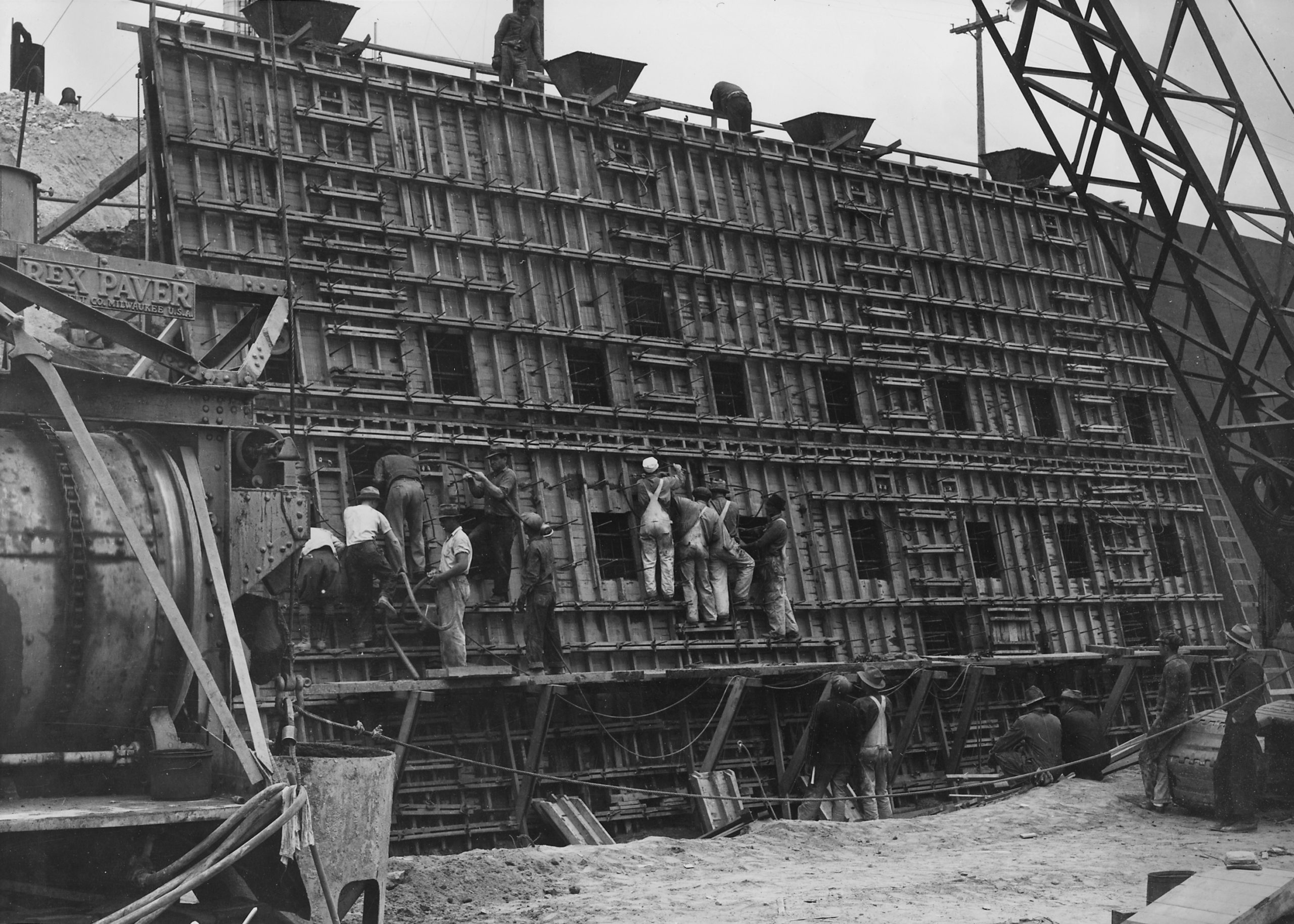

1938

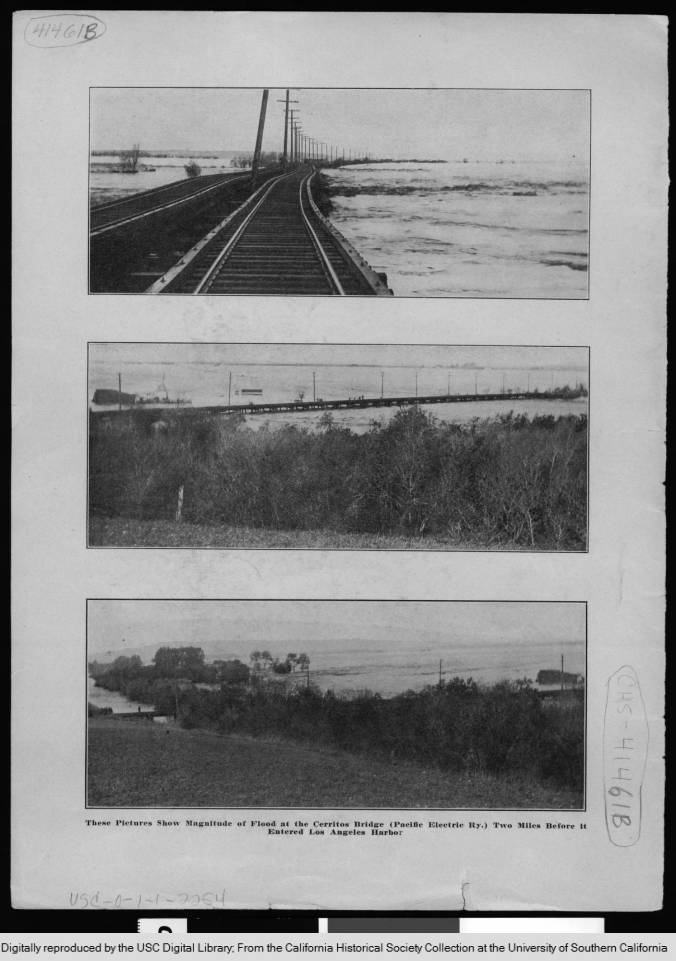

On February 27, a storm makes landfall off the coast of Southern California, drenching LA County with 4.4 inches of rain. On March 1, a second, more powerful storm hits the region with at least 10 more inches of rain.

What follows is a flood so catastrophic, it will alter the region’s landscape forever. The disaster kills as many as 115 people in Southern California, and causes about $78 million in property damage (or $1.39 billion in today’s money).

It is the worst flood in the region’s history – not only because of the amount of rain, but because the area has grown so quickly and without regard to the danger posed by its rivers.

Looking back in 1999, the Los Angeles Times will write: “Intense rainfall and flash flooding were as much a part of the region’s natural cycle as hot summers and Santa Ana winds…”

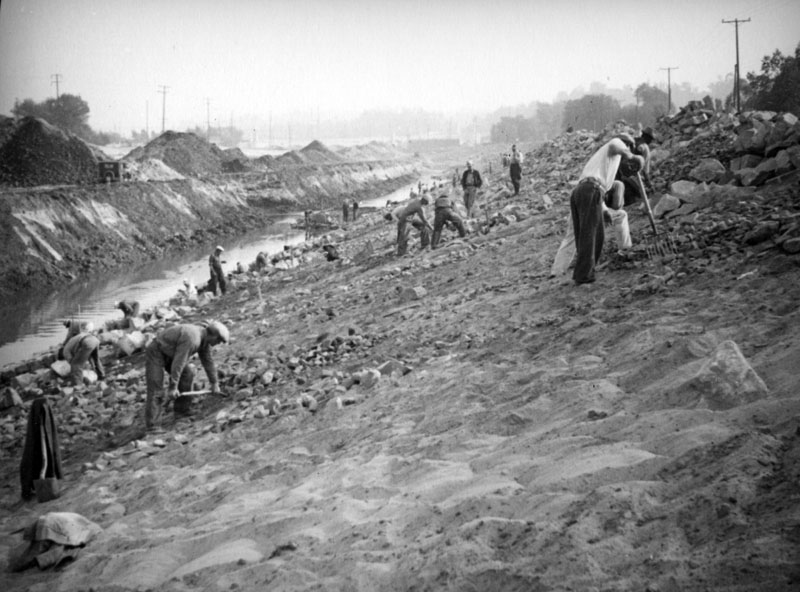

“Suddenly, the political will appeared to spend millions of dollars on a network of flood control dams and concrete channels that would become the Los Angeles area’s definition of a river.”

This work in the wake of the 1938 flood to channelize local river, construct dams, and build debris basins proves instrumental to preventing catastrophe in 1969 and 2005 when river volume exceeds those of the 1938 flood.

1959

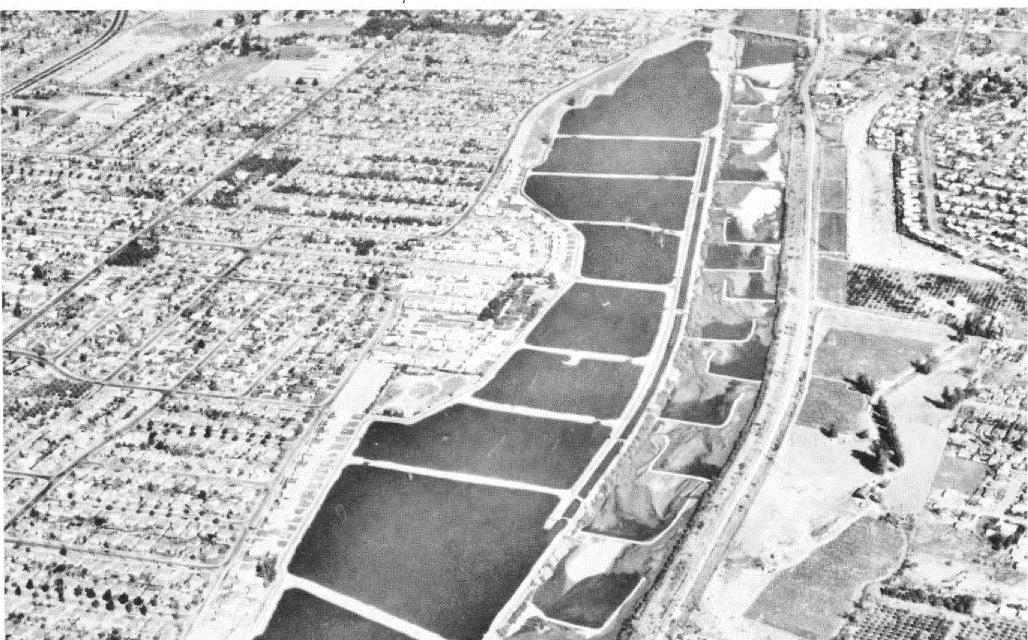

Southern California must address an urgent problem – the need to replenish groundwater basins. Groundwater had become a critical source of water for both drinking water and irrigating farmland. While strict laws exist for how much surface water – water from local rivers or constructed aqueducts – you can rightfully use, there are no such laws regulating how much water you can take from underground sources.

A growing population, increased demand, and little knowledge about how much water lies beneath the surface results in years of over-pumping. Some local groundwater wells go dry. In the search for more fresh water, others are dug so deep that ocean water begins slowly seeping into the groundwater basins – making the water undrinkable and unable to irrigate land. The problem is compounded by the fact that the basins have become harder to replenish. In the past, rainwater would flow through the mountains and seep into the ground into a groundwater basin. The proliferation of pavement in a rapidly urbanizing LA County greatly reduces organic groundwater replenishment and necessitates a new strategy to intentionally replenish these underground water sources.

In 1959, voters approve the establishment of the Water Replenishment District to manage and protect groundwater. Recycled water starts to be routinely used to recharge groundwater basins and the Flood Control District dispatches a complex system to capture stormwater so it can be used to help with recharge.

1960

Twenty-two years after they began, workers have moved 20 million cubic yards of earth, poured 3.5 million barrels of cement, placed 147 million pounds of reinforced steel and 460,000 stones, all in the service of transforming the region’s 278 miles of riverway beyond all recognition.

Some entities, like the Army Corps of Engineers and the LA Times, regularly refer to them as flood control channels instead of rivers. They are designed to carry water as quickly and as efficiently as possible from the mountains to the sea. They are freeways for water, a new metaphor for Los Angeles’s triumph over nature.

Three small sections of the 58-mile LA River are left semi-natural, with their beds unpaved: a piece behind the Sepulveda Dam in Van Nuys, an 11-mile section in the Elysian Valley called the Glendale Narrows and the river’s last few miles in Long Beach. These soft-bottom sections will, in time, provide the venues for the rediscovering of the river.

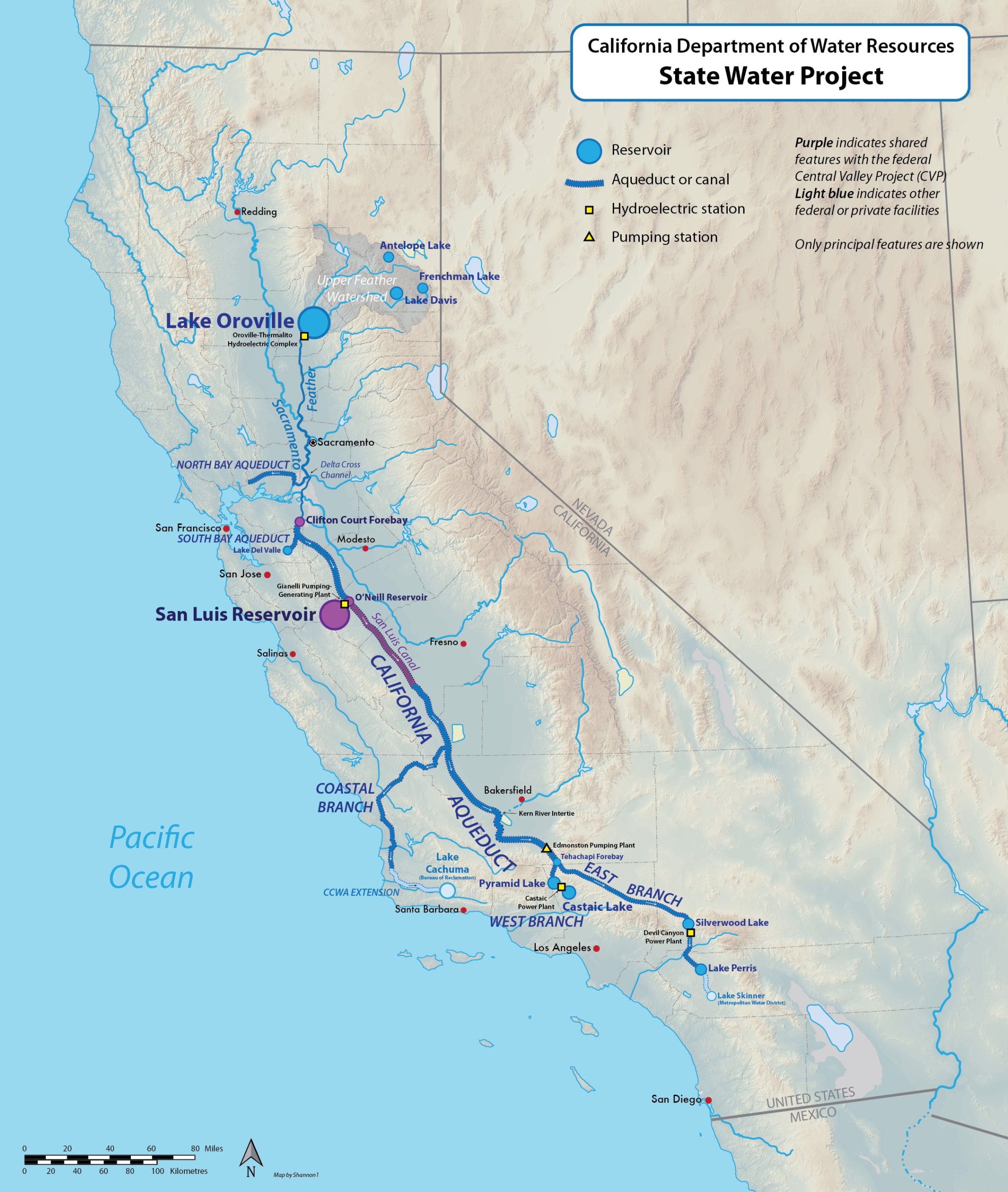

The project will create one of the largest public water and power utilities in the world, building a network of aqueducts, pumping stations and power plants over hundreds of miles across California.

Construction begins in 1961 and takes decades to complete. It will eventually become the #1 consumer of power in the State of California and comprise 21 dams (including the Oroville Dam), 34 reservoirs and more than 700 miles of canals, pipelines and tunnels.

Its purpose: take water from Northern California rivers, where water is plentiful, pump it thousands of feet high over the Tehachapi Mountains and deliver it to the comparatively arid Central Valley and booming Southern California region.

The SWP continues to expand as regulators weigh the need for more capacity with trying to mitigate ecological damage from water withdrawals in Northern California.

2000s

In the 21st Century, LA County is stepping up efforts to grow our local water sources through emerging technologies and improved infrastructure which will increase our capacity to capture and use stormwater, decrease water pollution, and open the door to the use of converted ocean water. Of critical importance is the need to balance diverse and sustainable water sources with programs that improve the efficiency of water use and encourage conservation of water resources.

2017

Between 2011 and 2017, California endures one of the most intense droughts in its history.

Among other devastating environmental effects, the drought kills 102 million trees; 62 million of them die in 2016 alone. Though the drought finally ends in 2017, scientists predict more dry stretches in the years to come, thanks in part to climate change. These droughts will test LA County’s water system, forcing all of us to conserve more.

Now

Facing the threat of continued climate change, LA County continues to adapt its water system. Water falls differently than it did 100 years ago – more rain falls in increasingly short periods, followed by long stretches with no rain at all. This, combined with our increasing population, deepens the strain on our water sources while our water infrastructure has become vulnerable to rising sea levels, extreme floods increased pollution, and the potential for earthquakes.